Mitral Valve Repair: It’s an Art

When the heart’s mitral valve works correctly, consider it a wonder of biological architecture.

“The mitral valve functions like two doors that open and close,” says Dr. Joseph Lamelas, chief of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Miami Health System. “When they connect together they look like a Roman arch.”

The mitral valve, one of four heart valves, is located between the left atrium and left ventricle of the heart and it controls the oxygen-rich blood flow from the lungs into the left ventricle — an important job because the left ventricle is the heart’s main pump. Like its sister heart valves, the mitral valve, as Dr. Lamelas says, has flaps that open and close with each heartbeat.

Sometimes, however, the beautiful architecture of the valve shows signs of wear and the valve doesn’t work properly. Surgery to repair or replace is often needed.

More than 5 million Americans suffer from some form of heart valve disease, including those with mitral valve issues, according to the American Heart Association. When a problematic mitral valve is shown to disrupt the way blood flows through the heart, “we recommend that the valve be fixed earlier than later,” Dr. Lamelas says.

For years, the accepted medical thinking was to wait for symptoms to appear. These include shortness of breath, fatigue, irregular heartbeat and swelling of ankles and feet. But surgeons and cardiologists have determined it’s best to fix the mitral valve before the disruptive blood flow can further damage the heart.

“We know today that it’s not a good idea to wait for those symptoms. The rate of long-term survival is diminished if we wait,” says Dr. Lamelas, a world-renowned pioneer in various forms of minimally invasive cardiac surgery, including his series of techniques called The Miami Method.

In fact, some patients might not experience symptoms for years. Many end up discovering a problem with the mitral valve during a routine medical visit, when a physician hears an abnormal heart sound through a stethoscope. When such a murmur is picked up, an echocardiogram is usually ordered to detail the function of the heart, including the health of the valves.

Mitral valve disease is characterized by the malfunction of the valve flaps. These either don’t close correctly, causing the blood to leak back to the left atrium (regurgitation), or they haves thickened or stiffened in such a way as to narrow the valve opening and reduce the flow from the atrium to the ventricle (stenosis). Causes can vary. Primary valve regurgitation, for example, is often caused by a valve prolapse, or the flaps swelling back into the left atrium. Secondary mitral valve regurgitation is caused by heart diseases, such as cardiomyopathy.

Valve problems inevitably result in serious health conditions. If left untreated, they can lead to complications, from atrial fibrillation to pulmonary hypertension, stroke, blood clots and heart failure. That’s why replacing or repairing the valve is essential. Some patients, however, may be reluctant to undergo treatment because they may be asymptomatic when diagnosed.

It’s hard to hear you need surgery when you feel just fine, but you want to fix it before the damage occurs to your heart muscle.

Dr. Lamelas

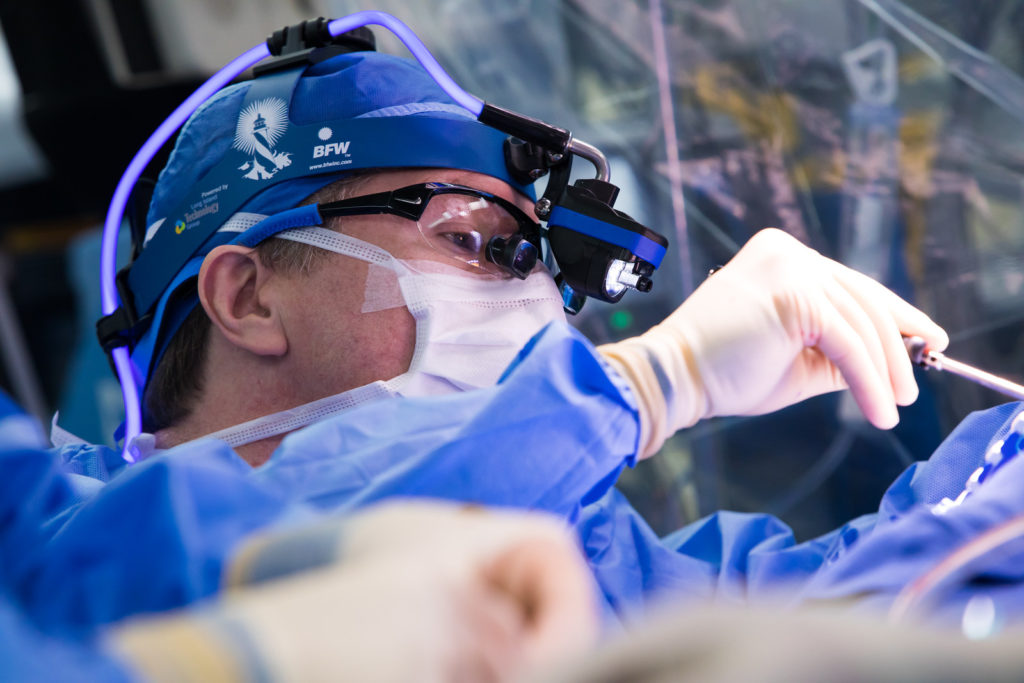

Traditional valve repair, or sternotomy, requires a large incision along the chest and the breaking of the breast bone, but Dr. Lamelas uses minimally invasive techniques that he has perfected over the years — a 5 cm incision on the right side of the chest and special instruments to reach through the ribs to work on the valve. Dr. Lamelas’s minimally invasive surgery has many benefits: shorter hospital stay, shorter recovery time, less pain and better psychological reactions to the surgery.

He tells patients and surgeons that, with the right technique, experience, and tools, a big incision is unnecessary. “Making the incision bigger does not make the valve any bigger,” he quips. The mitral valve is a mere 2-½ by 2 inches.

Operating on it in closed quarters, however, demands a dexterity that comes only with years of practice. Dr. Lamelas believes this surgery requires “a lot higher level of experience” than other valve repairs or replacements.

He performs more than 350 mitral valve surgeries a year. In comparison, the average heart surgeon performs five. “Mitral valve repair is not only a science but it’s also an art,” he adds. “It’s like performing plastic surgery on the valve.”

A valve repair can last about 25 years, a replacement valve 10 to 15. Dr. Lamelas also performs re-operative surgery on patients who have already undergone valve surgery, including those who previously underwent a sternotomy.

Guest Contributor

Ana Veciana-Suarez is a regular contributor to the University of Miami Health System. She is a renowned journalist and author, who has worked at The Miami Herald, The Miami News, and The Palm Beach Post. Visit her website at anavecianasuarez.com or follow @AnaVeciana on Twitter.

Tags: Ana Veciana Suarez, Dr. Joseph Lamelas, Miami Method, mitral valve