“Do Not Resuscitate” Tattoos: An Advance Directive Conversation Starter

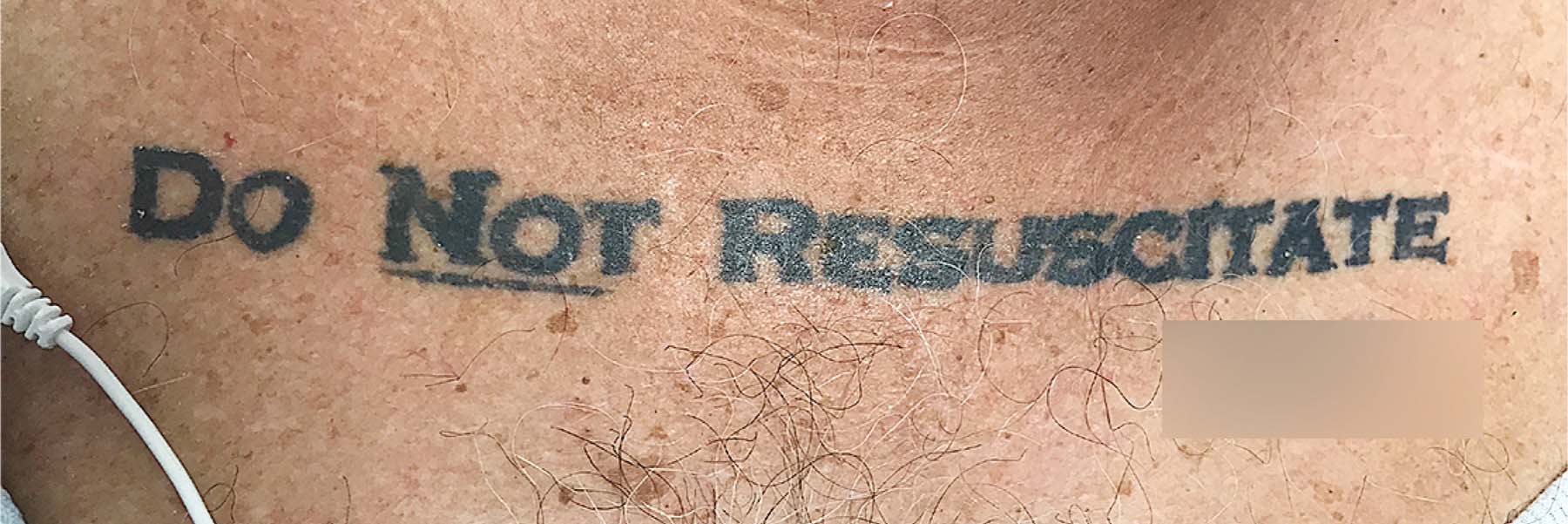

You may have heard about an unconscious patient who was admitted to a local ER last summer who had a “do not resuscitate” (DNR) tattoo on his chest, complete with his signature.

Without a next of kin to ask, the physicians at Jackson Memorial Hospital were unsure if they should – or could – honor it. So, they consulted the University of Miami’s Institute for Bioethics team, founded and led by Dr. Kenneth Goodman. After reviewing the case, the team concluded that they should honor the request of the 70-year-old patient who had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation.

Many people have specific wishes regarding their medical treatments and how they would like to die. This is especially true of older people who may have terminal cancer or other serious illnesses. But, how do you make sure that your end of life wishes are followed?

According to Dr. Goodman, patients legally have the right to informed consent and can refuse treatment if they choose. However, when a patient is unconscious someone else needs to consent or refuse for them. Often this is a family member or a friend. But when that is impossible, as was the case with the man with the tattoo, doctors are faced with difficult decisions. “We have had the ability to prolong life using technology for a while, but that doesn’t necessarily mean we should,” says Dr. Goodman. “This patient took extreme measures to send a signal that he did not want to be kept alive.”

Make your wishes known

You don’t have to go to extraordinary lengths to communicate and document how you would prefer to die. Instead, you can designate a proxy that can make decisions about your medical care and fill out a living will that lists your healthcare wishes.

“It’s important to have conversations with loved ones about end-of-life preferences, especially if you want a peaceful death at home with your family – and not in a hospital with physicians and nurses struggling to figure out those preferences and how to honor them,” advises Dr. Goodman.

Conversation starters

Sitting down and talking with people you love about death can be uncomfortable for all involved. If you aren’t sure where to start, the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization has an advance directive section on its website. According to them, there are more situations that can lead into a discussion about end-of-life desires than you would originally think – financial planning, the death of a celebrity, a touching movie or even this article can be used as a conversation starter.

Dr. Goodman suggests starting with a simple discussion about what you value most about life. “Most people when asked will say things like, ‘I like to read,’ ‘I enjoy speaking with my family,’ or ‘I love playing music,’” he adds. “It’s cognitive processes such as these that make us … us.” That may help you to begin defining under what circumstances you would refuse life support or decide not to be resuscitated.

Other things to keep in mind

- Your proxy can be anyone you trust and knows you well enough to make decisions on your behalf.

- Advance directive laws differ by state. You can find copies of your state’s directives here.

- Many states require a signature on an advance directive or medical power of attorney to be witnessed or notarized.

- Do not put your advance directive in a safe where it cannot be found. Make copies to give to your proxy, family members, physicians, spiritual advisors, etc.

- Check with your local hospital; it should keep them on file.

- Some states like North Carolina have online registries where you can file your directive and even print out a card you can carry.

- Revisit your advance directive regularly, especially if you have a change in health or family circumstances. You will need to fill out a new one should you have to make changes.

Natasha Bright is a contributing writer for UMiami Health News.

Tags: advance directives, do not resuscitate, living wills, medical ethics